Written by Felicity Tao, Chair of the Greater Cincinnati Chinese Cultural Exchange Association

Written by Felicity Tao, Chair of the Greater Cincinnati Chinese Cultural Exchange Association

Bringing the Chinese Railroad Workers Photography Exhibits to Cincinnati is part of my journey to claim American citizenship.

An immigrant from China, I became an American citizen three years ago. Growing up, I never thought of immigrating to another country. I completed my college education in China and decided to pursue graduate studies in the U. S. because American universities were known for their academic excellence and the country was perceived as a beacon for freedom and democracy. The Chinese of my generation admired the U.S. as a country exemplary of diversity, tolerance, justice, and prosperity. It’s known to attract talents from all over the world, and I was eager to embrace that experience.

My husband came to study Asian American history at the University of Cincinnati during the same time. Through his study, I was exposed to a fuller picture of Chinese American history, a history full of challenges, injustice, and triumphs. However, I read it as someone else’s history back then until my personal journey connected me directly to our predecessors’ painful struggle to claim American citizenship.

For generations, there has been this deep sorrow in the Chinese American community that no matter how hard we try, we are viewed as permanent aliens because of our appearance and cultural heritage. That sorrow couldn’t be felt more poignantly than the experience of the Chinese railroad workers who helped build the iconic, life-altering Transcontinental Railroad.

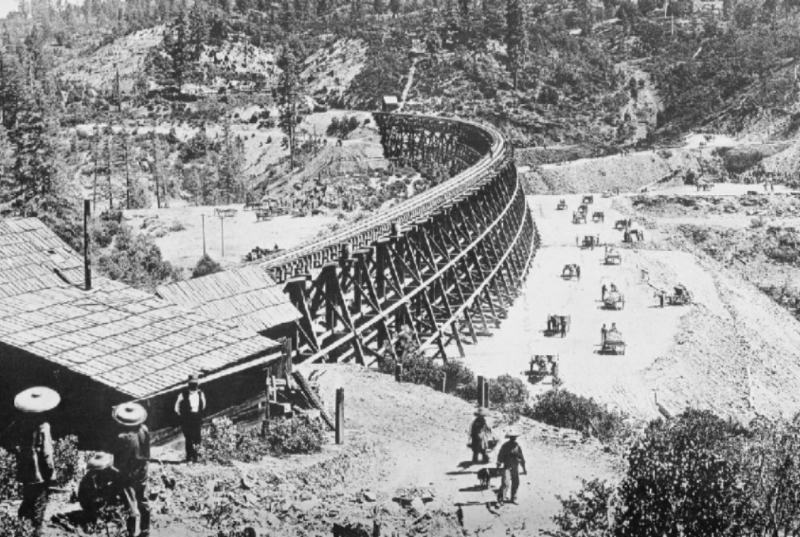

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 marked a profound transformation, shortening a dangerous months-long journey to cross the country to a week. It changed the economic, cultural, and geographical landscape of the country.

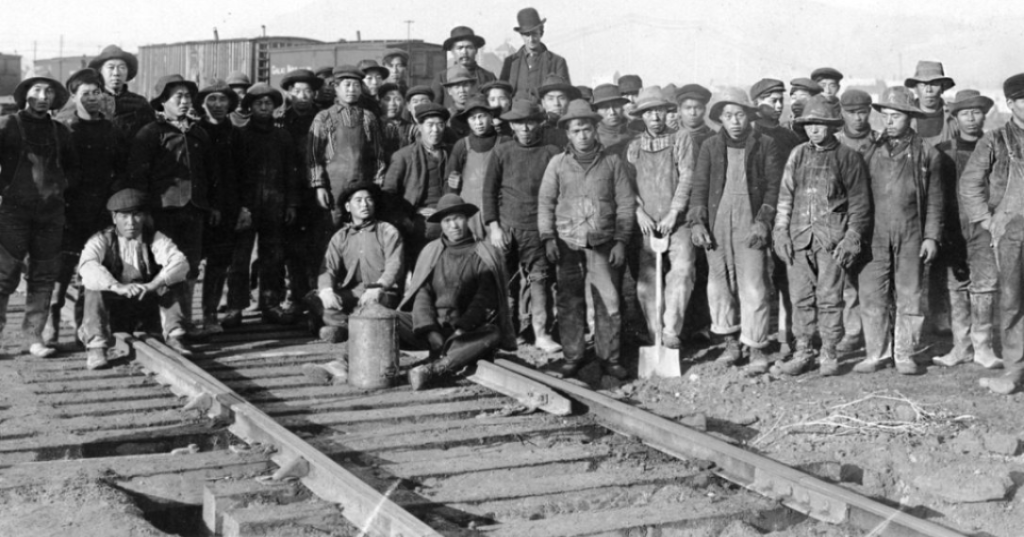

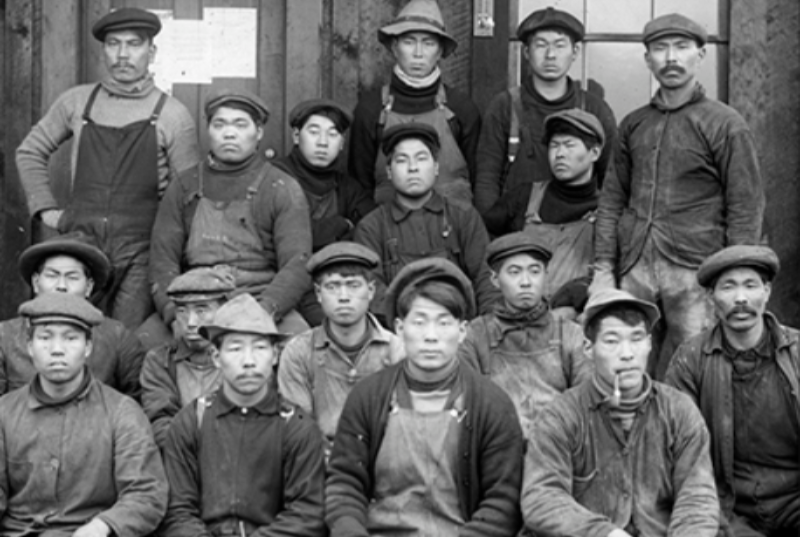

Between 1865 and 1869, more than 12,000 Chinese workers, who made up 90 percent of the Central Pacific line workforce, toiled at a grueling pace in dangerous working conditions to construct America’s first Transcontinental Railroad. They were hired because of a labor shortage following the Civil War, and they were constantly brought in as strikebreakers. When they too began to strike due to poor working conditions and little to no wages, their employer cut off their food and supplies until they went back to work. Hundreds died.

Most of these Chinese workers were all but invisible at the railroad completion ceremony, and in the telling of its history for many years afterward. Not only were they not recognized, but they were also openly discriminated against, vilified, and forgotten.

Once the U.S. had its fill recruiting Chinese workers to complete backbreaking labor, it enacted The 1875 Page Act which banned Chinese women from immigrating to the United States. It then implemented the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers. It’s marked the first law ever implemented to prevent all members of a specific ethnic or national group from immigrating, and it wasn’t completely overturned until 1965.

It’s no longer someone else’s history I can ignore. I still believe that the United States is a great country I decided to immigrate to, but I also can't deny its struggles. I was told not to speak Chinese on a bus when I was an international student 20 years ago. I was told to go back to China around my apartment building near UC’s campus. Last year, my husband and I celebrated our 20th anniversary in San Francisco, the first city we set our feet on in this country. We were walking on the street, looking for our hotel around Union Square when someone kicked my suitcase and hurled, “B****, hurry up. B****, go back to your country.”

Yes, much progress has been made since the Chinese railroad workers’ time. No, some things haven’t changed. I am in a sense a direct descendant from the railroad workers.

I met Monica Arima, the primary sponsor of the exhibits, at a support rally for Sherry Chen a couple of years ago. Sherry is an award-winning scientist at the National Weather Service whose work saved lives and properties. She was falsely accused of being a spy by her boss largely because of her Chinese origin. She fought hard to clear her name and won the case against the Department of Commerce but had her career and life destroyed in this process. Monica has a personal drive to tell minority histories to the general public because she believes we are equal Americans and our history should be remembered and told like anyone else’s in this country.

The descendants of the Chinese railroad workers worked tirelessly to correct the record of this part of American history. On May 10th, 1869, the leaders of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads came together to celebrate the joining of the tracks, and Leland Stanford, the business tycoon and political leader who founded Stanford University, drove a ceremonial golden spike into a tie to unite them. This spring at the Golden Spike Festival that marked the 150th anniversary of the Transcontinental Rail completion, the Chinese railroad workers’ descendants attended the re-enactment of this iconic moment in American history. Most importantly, they took the positions where their ancestors should have stood and recreated that famous photograph taken at the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the one with no Chinese faces.

My son, Teddy, who rides with me each morning for his summer internship downtown, was in the car with earbuds on when I heard the Golden Spike Festival story on NPR. I burst into silent tears when I heard one of the Chinese railroad workers’ descendants, Raymond Chong say: “Chinese were the perpetual foreigner, and we still are the perpetual foreigner.” I didn’t want Teddy to hear this. If he heard this, I would tell him this was not true. America is his home, his homeland. He can grow roots here and have equal opportunities to thrive. Every nation and every people have their struggles, and this is one of ours. We don’t have an option but to work hard to make it a little easier for future generations.

I hope the Chinese Railroad Workers Exhibits helps give a voice to the Chinese migrants whose labor on the Transcontinental Railroad made a big difference in this country and to the Chinese community that continues to contribute while struggling to be equal citizens. I encourage everyone in this region to take advantage of this opportunity to learn about our collective history and experience.

The Chinese Railroad Workers Exhibit is on display at the Downtown Main Library from August 1 - August 31, 2019. This exhibition is presented by the Greater Cincinnati Chinese Cultural Exchange Association (GCCCEA), the Greater Cincinnati Chinese School, the Cincinnati USA Convention & Visitors Bureau (CVB) via its Vibe Cincinnati platform and the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

Add a comment to: My journey to claim American citizenship