Written by James Mainger, Genealogy & Local History Reference Librarian, Downtown Main Library

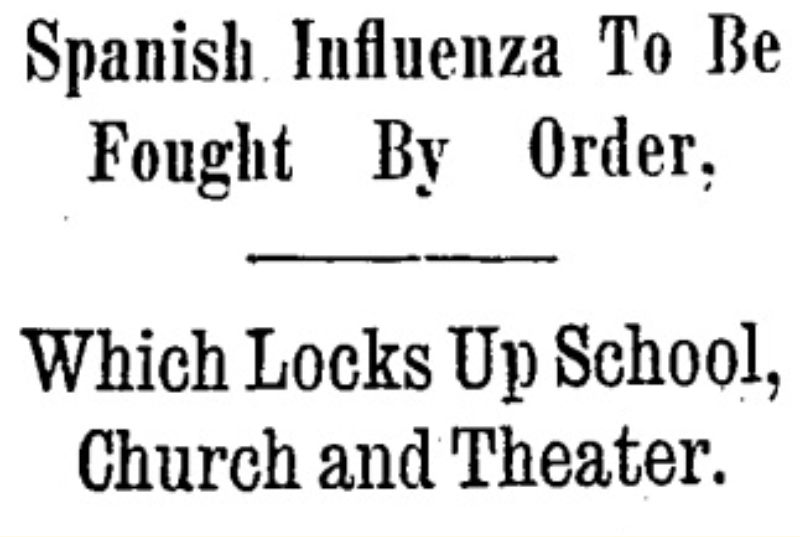

It was October 6, 1918, and Cincinnatians awoke to troubling headlines that the city’s Board of Health was so alarmed by the growing number of cases of the “Spanish” flu that it was considering a series of broad regulations to stop its spread.

Up until then the news from the battlefields of France, where American troops were part of a final push to end the war against Germany, had been the main thought on their minds, but this was soon to change. Reports of widespread influenza outbreaks in military training camps and in some cities had been in the news since the summer, but now the people of Cincinnati found it on their very own doorstep.

Throughout the month of October, Cincinnatians saw the numbers of flu cases and deaths rise higher and higher as health officials imposed stringent measures to slow the epidemic.

The first local death was of a wife of an Army lieutenant on September 27, who had become infected when visiting her husband at a training camp in Virginia. At first denying that there was an actual epidemic in Cincinnati, the city’s chief health authority, Dr. William H. Peters, initially proposed non-mandatory actions to prevent spread, but sharply changed course and called for compulsory restrictions.

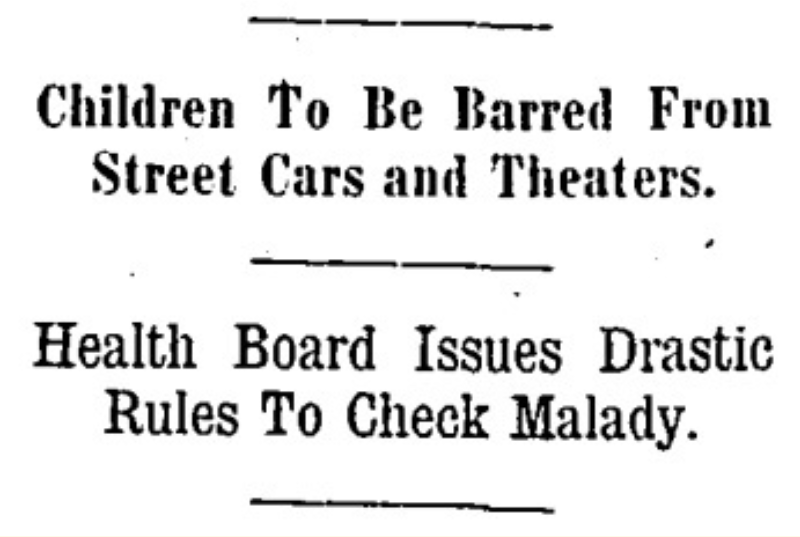

The Cincinnati Board of Health understood the value of both isolating the sick and general “social distancing” to stop the spread of a contagious disease. Visitors were banned from hospitals. Places where people crowded together were closed: all schools, live shows and movie theaters, houses of worship, and all inside or outside large gatherings.

The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County was closed, and all book lending halted. Most workplaces remained open, but employers were required to keep sick workers away. Stores and restaurants were kept open, however, and controversially, so were saloons, but only if they sold in bottles for drinking off-premise. That the saloons were even open at all while churches were closed irked many in the community.

Health authorities also recommended anti-contagion practices to the public, such as staying home if sick, covering coughs and sneezes, not visiting sick friends, and waving to your friends instead of handshakes. Surprisingly, hand-washing was not often suggested. Face masks, at that time made of gauze, were recommended for barbers and hotel workers but were never required for everyone to wear in public in Cincinnati as they were in some other cities.

Many heroic stories emerge from this time: of doctors and nurses working long hours and sleeping little to handle the overwhelming number of cases in the hospitals; of these same doctors and nurses becoming infected and in some cases dying of influenza; of medical students filling in at hospitals due to a wartime shortage of doctors; and of many ordinary citizens offering help and supplies. Many of the city’s firefighters became ill due to their greater public exposure and the cramped conditions in most firehouses.

Demands to relax the restrictions were rejected by the Board of Health in late October, when the number of new infections seemed to peak. But the signing of the Armistice November 11 brought the crowds out to celebrate America’s victory in World War I, and the board quickly ended all of the flu closures and regulations, as it turned out, prematurely.

The city saw a resurgence of influenza infections and deaths in the coming months. Re-opening the schools in particular spread the disease rapidly among children and forced a re-closure in early December. The epidemic eventually ebbed away over the next few months.

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19 infected a third of the entire population of the world and left an estimated 50 to 100 million dead, making it the deadliest pandemic in world history. The First World War accelerated the spread of this virulent new strain of influenza with crowded army camps and extensive movements of troops across regions, countries, and oceans, which spread the disease to the civilian populations around the globe.

Despite the domination of news about the war in the press, the United States lost 675,000 to the pandemic, far more than its 53,400 combat deaths from the war. Cincinnati alone experienced about 1,700 influenza deaths, but it is likely that the public health measures taken by city health officials, however imperfect, saved many lives.

Today, as our city along with the rest of the globe battles the COVID-19 (coronavirus) outbreak, we can take comfort in knowing that hard lessons from the past are being used to inform some of the measures taken today to flatten the curve and save lives.

While this road is paved with hardship and heartbreak, eventually this moment will become a part of our past, one that we can all hopefully reflect upon as a time when we came together as a community to support and fight for one another, weathering the storm together.

Further Learning - Genealogy & Local History YouTube Discussion

Further Reading

"Influenza."The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine, opens a new window

"Epidemics and Public Health." Dictionary of American History, opens a new window

Angela Woodward. "Flu Pandemic." Environmental Encyclopedia, opens a new window

"The Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919." American Decades , opens a new window

For the latest Library service updates and resources, please visit our COVID-19 resource page, opens a new window.

Add a comment to: Lessons from the past: Cincinnati and the 1918 flu pandemic