Written by Eli Grey, Digital Services Assistant, Genealogy & Local History Department, Downtown Main Library

On the first Thursday of each month, our Genealogy and Local History Department "throws back" to a time in Cincinnati's history that is featured in our Library's wide-ranging collection of more than 9 million materials.

George Remus was a German immigrant who grew up in Chicago. From an early age he began supporting his family, due to his father’s alcoholism, by working at a pharmacy. He worked his way up until he owned several pharmacies and was a pillar of the community. He studied law and began championing labor rights and immigrant causes as well as criminal cases. Remus loathed the death penalty and justified any means of preventing his clients from execution. His charisma and intelligence turned many of his court cases into high drama— he became a favorite of the newspapers and earned the nickname “Crying Remus.”

A Whole Lot of Drama

Then Remus met a woman who reveled in drama as much as he did—Augusta Imogene Holmes. Both of them were married at the time, but they divorced—Imogene finalizing hers after embellishing the truth to the press, Remus after being caught with Imogene years later—and married in 1920.

After Prohibition, his defense clients included bootleggers. He saw how easily money could be made, and his knowledge as a pharmacist and lawyer made him realize potential loopholes he could exploit. He could legally buy liquor and "steal" it from himself to resell at a huge profit. He moved to Cincinnati because most of the nation’s whiskey was within 300 miles of it and began his bootlegger business. He bought up local distilleries. He did not dilute his liquor—a common and sometimes dangerous practice—but nothing barred those who bought it from doing so.

Bigtime Bootlegger

He rapidly acquired a huge fortune and a lot of influence. Remus and Imogene reimagined themselves: Remus referring to himself in the third person, lavishing upon those he liked and raging at those who went against him, proclaiming he never drank while surrounded by booze; Imogene as a daring fashionable flapper at the center of everything. Imogene was his partner in helping him hide his riches since much of their fortune was in variations of her name. At its peak, a third of the nation’s liquor went through their operation.

Many people loathed Prohibition, which disproportionately targeted immigrant, urban, and minority communities. Remus brazenly defied the law and had many local employees, establishing him as more folk hero than criminal. Bribed officials meant he rarely ran into trouble with the law.

But it didn’t last.

The Hard Fall

A push for stricter Prohibition enforcement and the attention of the most powerful woman in the country, Assistant Attorney General Mabel Walker Willebrandt, finally got Remus into trouble that bribes couldn’t fix. He was convicted and sentenced to multiple jail terms.

Being in prison didn’t quash his liquor empire. Willebrandt, who had difficulty finding honest agents, sent in one of her best to gather information. His name was Franklin Dodge. Remus, thinking Dodge was a potential ticket out, told his wife to get to know the agent and dropped hints that he’d be willing to testify against other bootleggers.

He started hearing that his wife was cheating on him with Dodge but refused to believe it. Willebrandt also heard and investigated. Their suspicions were quickly proven correct. Imogene served Remus divorce papers the day he was to transfer to his next jail sentence, and made plans to have him deported or killed. Imogene and Frank sold off Remus’s fortune, gutted his lavish mansion down to the stone lions and chandeliers, and left him with only $100.

A Grisly End

Remus filed his own divorce suit and spoke with reporters often about Imogene’s misdeeds. He had been lavish with his pet names and was just as effusive tearing her down—repeatedly refusing to use her name, calling her “degenerated clay” or other dehumanizing language. Dodge received similar treatment from Remus; he was called Imogene’s pimp, a moral leper, and a human parasite.

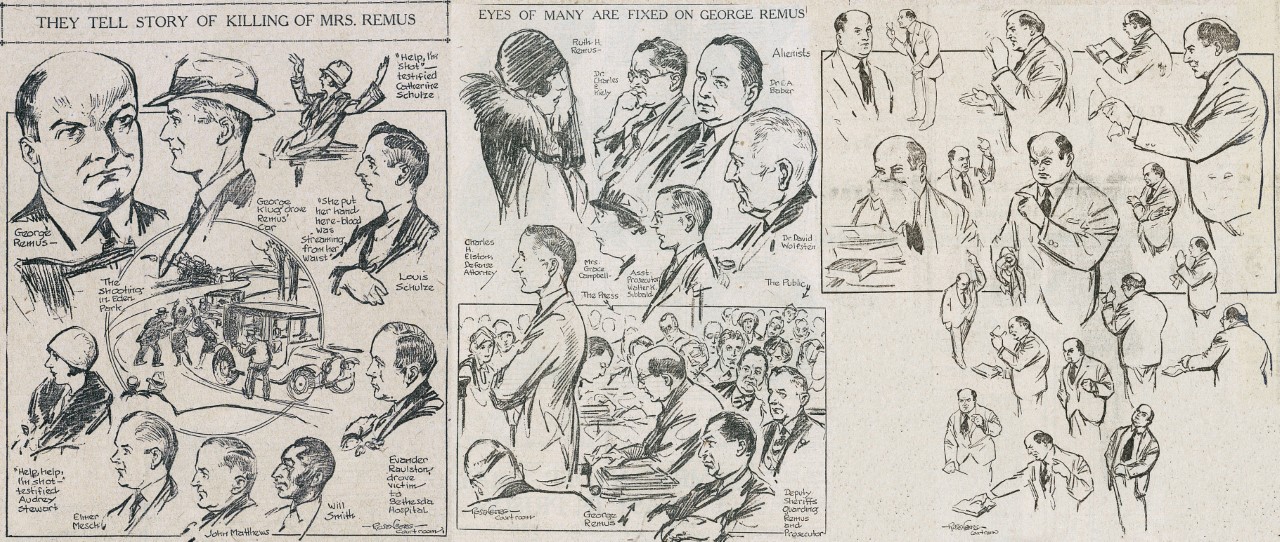

The day they were to finalize the divorce, Remus sought out Imogene saying he wanted one last chance to speak to her. Upon seeing Remus, Imogene panicked. A car chase ensued ending in Eden Park. After a brief argument, Remus shot Imogene in the stomach. She died soon after. Remus turned himself in at a police station. The news made the front page all over the country and the trial continued to be front-page news for the next two months.

She Said, He Said

The defense portrayed Imogene as a woman terrified of her violent husband, wanting to testify against him and killed for knowing too much. The prosecution presented a woman who had willingly participated in bootlegging and enjoyed its spoils, betrayed her husband for a corrupt government agent, stole her husband’s assets, and tried to have him killed.

Remus’s first wife, who had accused him of physical violence and cruelty when they divorced, painted Imogene as an obsessed gold digger and declared it “self-defense.” Remus’s many visitors during his time in jail and at his gutted mansion attested to a man distraught from betrayal. Remus repeatedly had outbursts or broke down in court. He claimed it was morally justified to act as he did. The newspapers printed it all.

Charles Taft, son of President William Howard Taft, was just shy of 30 and considered a rising star as a county prosecutor. He struggled to sway the jury with dry evidence instead of emotional appeals. Even if he got Remus’s remarks struck after the fact, they still planted doubt. He made some major missteps, such as trying to tie Remus’s secretary and driver as fellow conspirators of a coldly calculated murder. Dodge repeatedly denied having an inappropriate relationship with Imogene despite the evidence, which didn’t help his credibility.

Drama 'til the End

The jury—mostly men, all named in the local papers— deliberated only 19 minutes. They sided with Remus and said they would’ve acquitted him entirely if allowed. They petitioned the judge to have him home for Christmas, who rebuked them and demanded an apology. The trial was seen as judgement of Prohibition more than the murder, and Cincinnati’s German population was blamed for the verdict.

Remus was deemed insane and sent to an asylum. He was able to get declared sane soon after; the evaluation process was the only time he expressed any remorse for the murder. Afterward, the Cincinnati Bar Association made changes to the jury selection process in hopes of never having a repeat of the Remus trial fiasco. Those involved lived quietly after the trial, not making headlines again.

You can read about the life and times of George Remus in two recent books in the Library’s collection:

You also can see George Remus portrayed by actor Glenn Fleshler in the TV series Boardwalk Empire, available on DVD from the Library.

Read more Throwback Thursday blog posts from our Library's our Geneology and Local History Department.

Add a comment to: Throwback Thursday: Cincinnati’s Most Notorious Bootlegger, George Remus