Written by Community Contributors Sulin Ngo & Maki B. Somosot

Written by Community Contributors Sulin Ngo & Maki B. Somosot

In the context of the Asian American experience, what does feminism mean? As two Asian American women—Sulin, born in the U.S., and Maki who immigrated as a teen—both leaders in community spaces, we sat down to talk about what feminism means in the context of our Asian American experience.

What does Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) feminism look like?

Maki: When I first heard about feminism or encountered the word, I already had this image in my head that was like, these bohemian white women with hairy legs that were chaining themselves to something that shouldn’t be cut down. I always kind of recoiled at it because public perception paints feminists as crazy women who just don’t conform.

Sulin: Right, my first introduction to feminism was from an older white male American history teacher in high school who only referred to feminists as “feminazis”—not a great first impression. Even though I went to a liberal arts college, my understanding of feminism then was still very underdeveloped: “Oh, my female professor doesn’t shave her legs and that’s radical.”

Maki: I ended up studying postcolonial literature in college and a lot of texts that we read were very feminist in nature, and it was fascinating because it reframed feminism from the perspective of a different culture. In that context, feminism wasn’t always the big radical acts—it was these subtle, powerful ways of disrupting the status quo, like Arab women protesting with the way they wore their hijabs. Or quietly breaking the status quo in their writing.

Sulin: Feminism may be as simple as learning to survive—and succeed—in a world that wasn’t designed for you to do so. I’ve realized that my mother is probably the closest real example of a feminist that I have, which seems obvious, right? She was a single mom, the breadwinner, and a female leader in our community. But it took me a long time to understand that her strength as a woman was also connected to her Asian-ness—immigrating to a new country, learning a third language, getting her third degree in that new language, and doing it all while navigating the undertones of racism we’d encounter in checkout lines or at PTA meetings.

Maki: I come from a family of very strong women, and in the Philippines we had women presidents, so it wasn’t a big deal like it is here. Watching my single mother work abroad to pay for my and my sister’s private school educations gave me so much more appreciation for the ways in which you can be a woman and a feminist – and not fit the tree-hugging, unshaved-legs image. You can simply be an everyday Filipino woman who must provide for her family because there’s no one else to do it.

Sulin: So, I want to share this excerpt from Dragon Ladies: Asian American Feminists Breathe Fire by Karin Aguilar-San Juan, which I think helps set some groundwork for our readers—who may also think of AAPI feminism a certain way. Aguilar-San Juan writes,

“I have heard too many community activists explain the intersection of gender and race by referring to disembodied identities, fractions of human experience: ‘First I am a person of color, then I am a woman. That makes me doubly oppressed.’ According to this way of adding, a white man has the most whole identity; his experience is treated as the norm. The notion that the Asian American women’s movement consists of ‘two movements in one’ relies on this convenient but unreasonable arithmetic. Instead, Asian American feminism is an articulation of the necessary overlap of many social and historical processes of hierarchy and injustice.”

Maki: I like this different sort of dragon lady that’s emerging, not the seductive, malicious trope that Hollywood defined us to be, but one that breathes fire.

Sulin: Right? My Zodiac sign is the dragon, and I’m also the firstborn child of my family. And then to be the firstborn daughter of a single mom, there’s a certain expectation of strength because, in effect, you are the leader of your household under your mom. And I think that shaped my feminist views, because if I can be a leader in this way, in this space—why not anywhere else? And the answer to “why” is shaped by these social/historical processes and disembodied identities that Aguilar-San Juan talks about.

Maki: I really love that you said that about being first-born because, as you know, in Asian cultures, being firstborn means you have to set the example. I was also the firstborn child and grandchild in our family, so I had to be the strong one, the leader. But I didn’t always live up to those things—in fact, I was pretty mischievous as a kid.

For me these days, being first is not just about birth order, but the multitude of experiences that shape you and ultimately give you the ability to break out and be your own kind of leader. Because my mom had the opportunity to immigrate to the U.S., I also have the unique opportunity to pave my own path instead of being subordinated to typical familial expectations, like managing the family business in the Philippines and dealing with everything that comes with that. Here in America, I have this opportunity to break out of the bonds of intergenerational trauma and say “yes” to all of my quirks, achievements, and weaknesses—to all of my humanity. So that’s how I look at being first.

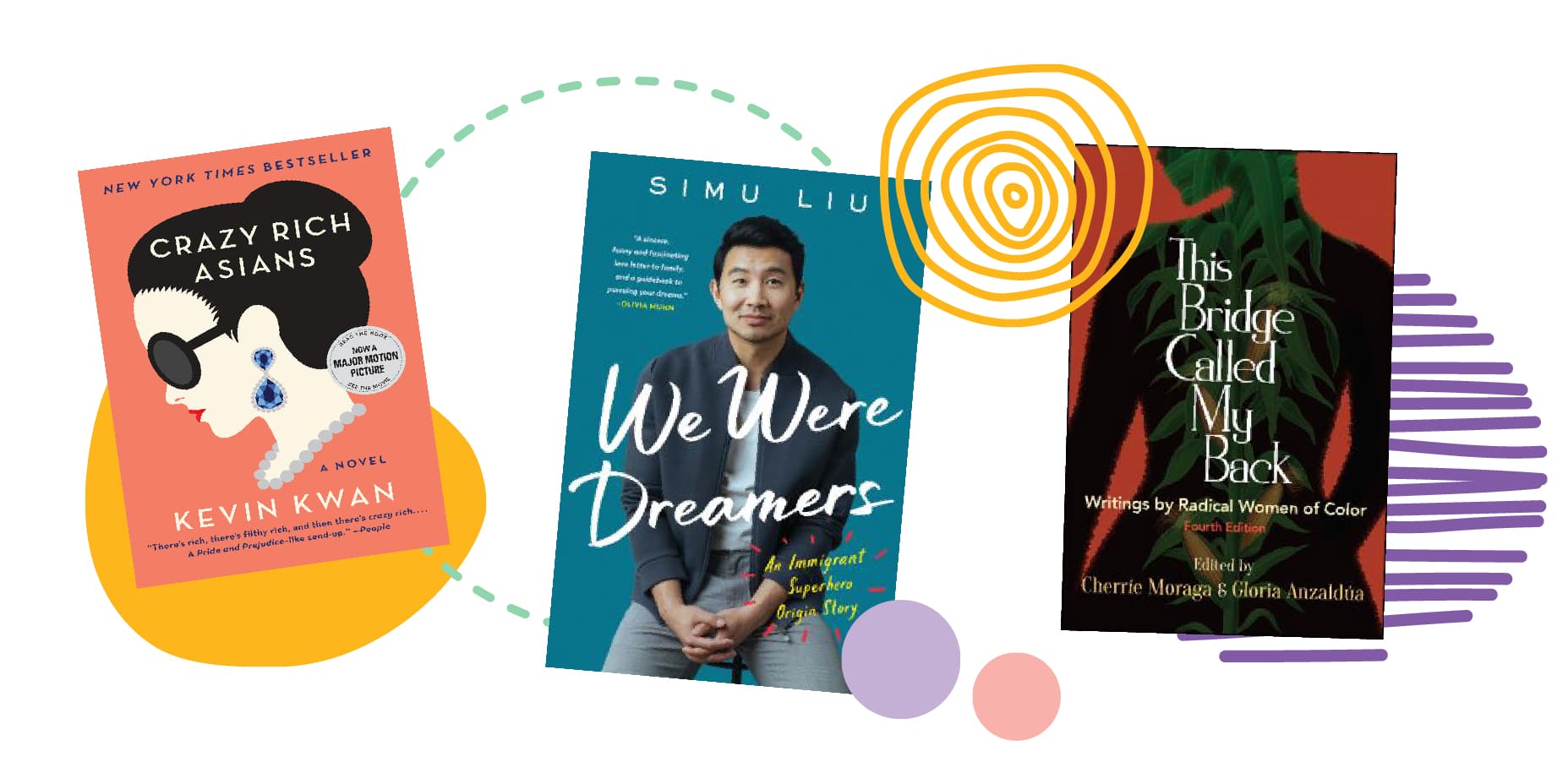

Sulin: As Asian Americans in the Midwest, it often feels like we’re “firsts” all the time – first Asian Americans, first women, AND first Asian American women in any given space. When that gets lonely, I have to remind myself that I’m not actually the “first” in the grand scheme of things. So many others have paved the way ahead of us. Like Michelle Yeoh. She’s not the first Asian American actress, but she feels like the first in a lot of ways due to some of the “first” movies she’s been in recently, like “Shang-Chi” and “Crazy Rich Asians.”

I love an interview that she gave, talking about the intentionality of naming her character Evelyn in “Everything Everywhere All at Once,” when it was originally supposed to be “Michelle,” because she wanted to give that character the ability to stand on her own. In the way Michelle’s been intentional in executing her craft and her deliberate choice of roles, she’s really opened the doors for the rest of us in how we choose to represent ourselves.

Maki: The real key there is intentionality, right? What sort of things from your experience are you choosing to elevate so that other people can see themselves reflected in your story?

Sulin: And what are the kind of roles we want to play? Although we come saddled with a lot of expectations of being “first,” we can acknowledge that just living as an Asian American woman and being present in certain spaces is radical in and of itself.

Maki: Quietly revolutionary. It’s important for us—as community activists and organizers—to contextualize because we’re active in campaigning for changes at the local, state and federal levels. It’s easy to fall into that trap of thinking our feminism is only valid if it’s limited to making these huge systemic changes through our activism. But feminism also means raising children who value the strength of women or marginalized genders, races, and identities. It’s in the decision our mothers made to raise us in another country and deliberately ignore the racists behind the counter because the priority was just getting that food on the table.

Sulin: My mom has an engineering degree from a prestigious university in China, and it’s very competitive to even go to a university in China, even when she was growing up. So, she has an engineering degree and when she came to the U.S., employers would not recognize her degree. It was either going back and getting another four-year degree in engineering or picking a different field. She went into nursing, which is backbreaking work.

But, the point is that she made the choice to do the backbreaking work of becoming a nurse, which allowed her to provide for her children and in those decisions where she made that choice, she created more choices for her daughters. In that sense, I see my mother as being a feminist because she believed that we could have choices.

Maki: You’re going to make me cry. I see my mom's story a lot in what happened with your mom. She came to this country as a Filipino woman who was very highly educated, had worked in diplomacy and the corporate world, had two master's degrees and two bachelor's degrees, and also spoke Japanese like no other. And then she comes to this country and tries out for this flashy corporate job in New York and doesn't get it because it goes to a white man. She's left scrambling and wondering how to provide for us.

Her situation was a little different than yours because she had my stepdad to help provide, but she also encountered a lot of racism from his family (who were ironically part-Filipino). When you talk about the racists behind the counter, it's not just the ignorant strangers who pass you by on the street, it’s also the people in your family and your community, the people who are supposed to accept you.

My mom endured that for us, so my sister and I could go to these elite colleges and do all these things. As you said, it’s a choice to leave behind everything you know and everything you consider yourself to be, because you believe it will give your daughters better choices.

Sulin: Yeah. It’s a good way to think about why AAPI feminism is necessary and necessarily in its own category—what kind of choices are uniquely available and unavailable for Asian American and Pacific Islander women, and what can we do about that?

To wrap up our conversation, here’s a quote from our favorite AAPI intersectional feminist activist, Grace Lee Boggs, who explains what AAPI feminism means to her: “As a child of immigrant parents, as a woman of color in a white society and as a woman in a patriarchal society, what is personal to me IS political.”

What does Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) feminism look like to you? Revisit our live panel, storytelling events, and community-wide discussions with video recordings and library materials with this blog post.

Add a comment to: Dragon Ladies, Michelle Yeoh, and Being First: What AAPI Feminism Means to Us