Written by Carey Hoffman, Ohio Innocence Project Director of Communications and Jennifer Bergeron, Assoc. Professor of Clinical Law/Deputy Director, Ohio Innocence Project, University of Cincinnati College of Law

Written by Carey Hoffman, Ohio Innocence Project Director of Communications and Jennifer Bergeron, Assoc. Professor of Clinical Law/Deputy Director, Ohio Innocence Project, University of Cincinnati College of Law

Wrongful convictions are not just the stuff of true-crime programs and podcasts. They happen everywhere, and Ohio is no exception.

To date, 28 Ohioans have had their freedom restored at least in part as a result of the Ohio Innocence Project, opens a new window (OIP) since OIP’s founding at the University of Cincinnati College of Law in 2003. There is a good reason to believe that right now, within OIP’s offices, overlooked details in cases are being identified that will become the backbones of Ohio’s next exonerations.

Throughout this summer, 22 law students are digging deep within case files and court transcripts as OIP Fellows, combing through cases that Ohio inmates have submitted for consideration and that OIP staff have screened for having the best chances for success.

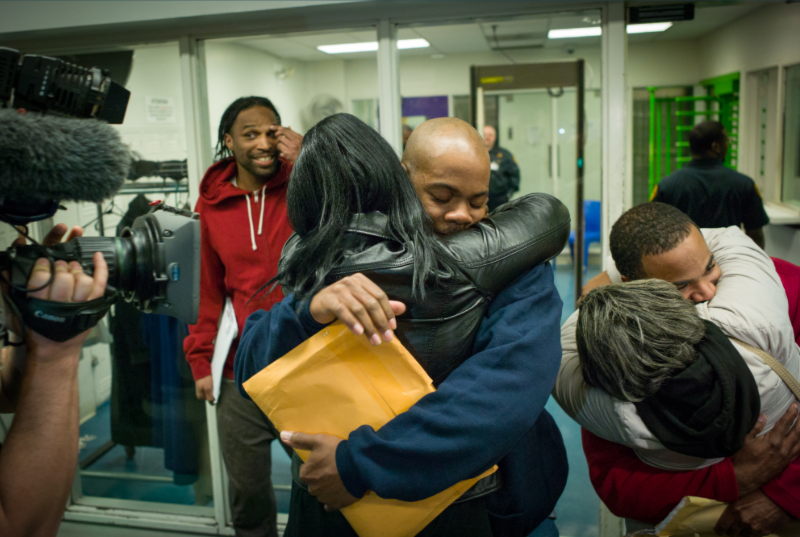

Ohio Innocence Project Fellows and exonerees on the day Chris Miller was released.

Ohio Innocence Project Fellows and exonerees on the day Chris Miller was released.

In 2018, OIP had two exonerations including Chris Miller of Cleveland. In June of 2019, Chris celebrated the one-year anniversary of his Freedom Day. His first grandchild arrived that same week. OIP attorney Jennifer Bergeron offered this reaction upon seeing a picture of Chris holding his granddaughter: “The defeats are stunningly difficult, but it is moments like this that keep me going.”

On those good days, when years of effort are rewarded by returning freedom to a wrongfully convicted individual, you end up with stories like:

- Clarence Elkins – Wrongfully convicted in 1999 of murder and sexual assault in Barberton, Ohio, Elkins served six years before DNA evidence earned his release 10 days prior to Christmas in 2005. It was a particularly hard-won victory, though. The first round of DNA testing proved Elkins was not the perpetrator of the crime. Despite proving that Elkins was not the perpetrator, the prosecutor refused to concede that this cleared Elkins. It was not until Elkins and his supporters brought DNA evidence establishing the identity of the true perpetrator to the prosecutor that Elkins was reluctantly released and cleared.

- Rickey Jackson – When he was released in 2014, Jackson held the unfortunate distinction of having been the longest-serving exoneree to that point in U.S. history. He was just 18 in 1975 when he and two friends, brothers Ronnie and Wiley Bridgeman, were convicted of the robbery and murder of a salesman in Cleveland and sent to Death Row. Jackson came within a few weeks of being executed before his conviction was commuted to a life sentence. It wasn’t until 2011, though, when a magazine reporter first reexamined details of the case that the conviction began to fall apart. Witness coercion and withholding of evidence favorable to the defense put Jackson on the path to exoneration after 39 years behind bars.

The exonerated East Cleveland 3 being released.

The exonerated East Cleveland 3 being released.

- Nancy Smith -- A former Head Start bus driver in Lorain, Ohio, Smith was caught up in the daycare child-sex abuse hysteria that swept throughout the nation in the 1980s and early ‘90s. The accusations in the case were so full of holes and lacking in corroborating evidence as to appear absurd. Still, a jury convicted Smith and a co-defendant. She was imprisoned for almost 15 years before a judge set her free in 2009.

- Laurese Glover, Eugene Johnson and Derrick Wheatt – Collectively known as the East Cleveland 3, these men were convicted as juveniles for a 1995 murder. The convictions were built on eyewitness testimony and gunshot residue evidence that police said was present on two of the men. Johnson was briefly released after winning a 2004 appeal for a new trial, but that ruling was overturned in 2005. Altogether, the three served 20 years before a combination of suppressed evidence that could have cleared them, prosecutorial misconduct and advances in gunshot residue analysis led to prosecutors dismissing the charges against them in 2016.

The stories of these exonerees take center stage in an unexpected venue this month. Their actual words describing what they have been through form the lyrics to songs in Blind Injustice, opens a new window, a world-premiere opera based on a book of the same name by OIP co-founder and director Mark Godsey. The production by the Cincinnati Opera is playing to sold-out audiences at Music Hall.

Five of the six exonerees whose stories are told in the opera 'Blind Injustice'.

Five of the six exonerees whose stories are told in the opera 'Blind Injustice'.

Understanding at a personal, emotional level what wrongful conviction is actually like for those who endure it is beyond most people’s imagination. Meeting exonerees in person and hearing their stories helps.

When his 39-year ordeal ended, Rickey Jackson said, “I’ve looked over the abyss and gotten to the point where I didn’t know if I was going to be able to live another day. But I always had that ember inside of me, that truth. I knew who I was. I wasn’t going to let this circumstance define me. I wasn’t going to be the criminal they labeled me to be.”

The National Registry of Exonerations, opens a new window reports that 2,471 exonerations have occurred across the United States since 1989. With approximately 50,000 inmates in Ohio’s prisons and a national estimated wrongful conviction rate of somewhere between 2-4 percent, the math suggests another 1,000 to 2,000 innocent people could potentially be currently serving time in our state.

Identifying people and working to win their freedom is arduous work for all involved. A typical exoneration can require a decade or more of time. OIP has many supporters and a dedicated, outstanding legal staff which includes seven attorneys, along with the hundreds of law school grads who have been OIP Fellows. It’s been said many times over by graduates of the program that this is the truest introduction they get to actual day-to-day lawyering in law school.

Ohio Innocence Project co-founder Mark Godsey with OIP exonerees.

Ohio Innocence Project co-founder Mark Godsey with OIP exonerees.

OIP Fellows are assigned a set of cases, and then they have to review voluminous trial transcripts and other case documents to determine whether a case is eligible for acceptance. They communicate with applicants and their families, which can include visiting applicants in prison face-to-face.

It is hard work, but those who have had the OIP experience will also tell you it is an amazing moment to see someone you have advocated for regaining their freedom. In some cases, it’s enough to make you sing. The evidence for that can be found this month at Music Hall.

Join attorneys and exonerees from the Ohio Innocence Project to hear their stories and learn more about OIPs efforts to free innocent people in prison and prevent wrongful convictions at 'Wrongfully Convicted: Stories from the Ohio Innocence Project'. Thursday, July 25, 2019 at 7 p.m. in the Harriet Tubman Theater at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, opens a new window.

After attending this event, plan to attend the Mary S. Stern Lecture with Bryan Stevenson, which will be held on October 2, 2019 at the Aronoff Center for the Arts. $5 Tickets will go on sale in early August. For more information, visit the Library Foundation website, opens a new window.

Add a comment to: The Ohio Innocence Project fights for justice and liberation