Written by Whitney Reynolds, Digital Services Assistant, Downtown Main Library

Written by Whitney Reynolds, Digital Services Assistant, Downtown Main Library

On the first Thursday of each month, our Genealogy & Local History Department "throws back" to a time in Cincinnati's history that is featured in our Library's wide-ranging collection of more than 9 million materials.

Tradition!

Early in the 19th century, a Jewish settlement grew in Cincinnati. Thanks to the Ohio River, the city’s industry was growing and it was quickly becoming a major manufacturing and commercial center. Most Jews came to Cincinnati for economic growth, but the first Jewish settlers struggled to maintain a traditional Jewish life.

Communal prayer, for example, requires a minyan of 10 men. A kosher butcher is necessary for providing meat and every Jewish community needs a rabbi. Traditional funerals require a wooden box and shroud. Out of necessity, one of the first Jewish communal organizations in Cincinnati was the burial society and communal cemetery. As the population in Cincinnati grew, synagogues and schools were created. By mid-century, Cincinnati had its first rabbis and discussions quickly began about how to live a Jewish life in post-frontier Cincinnati.

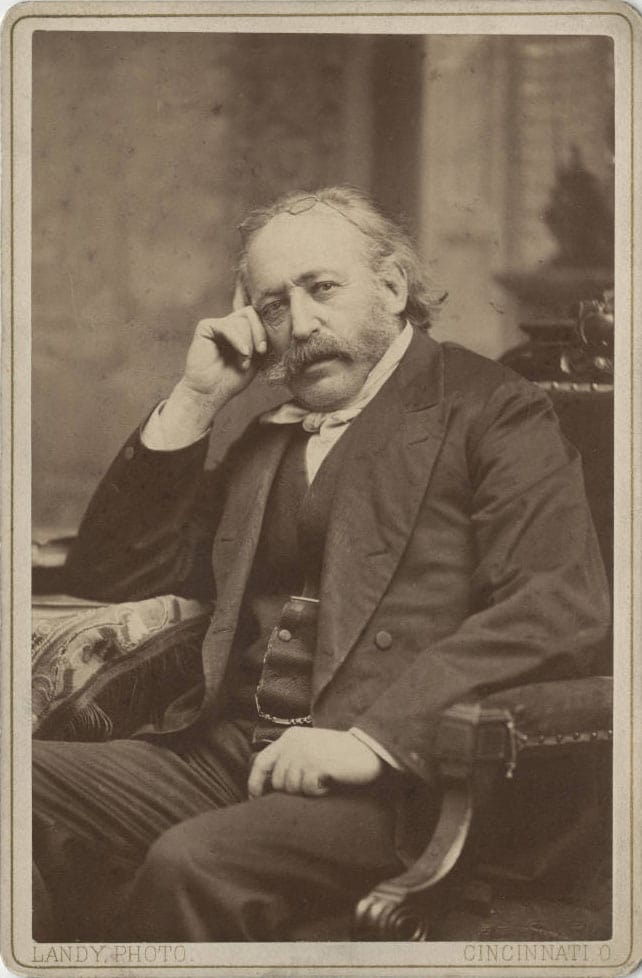

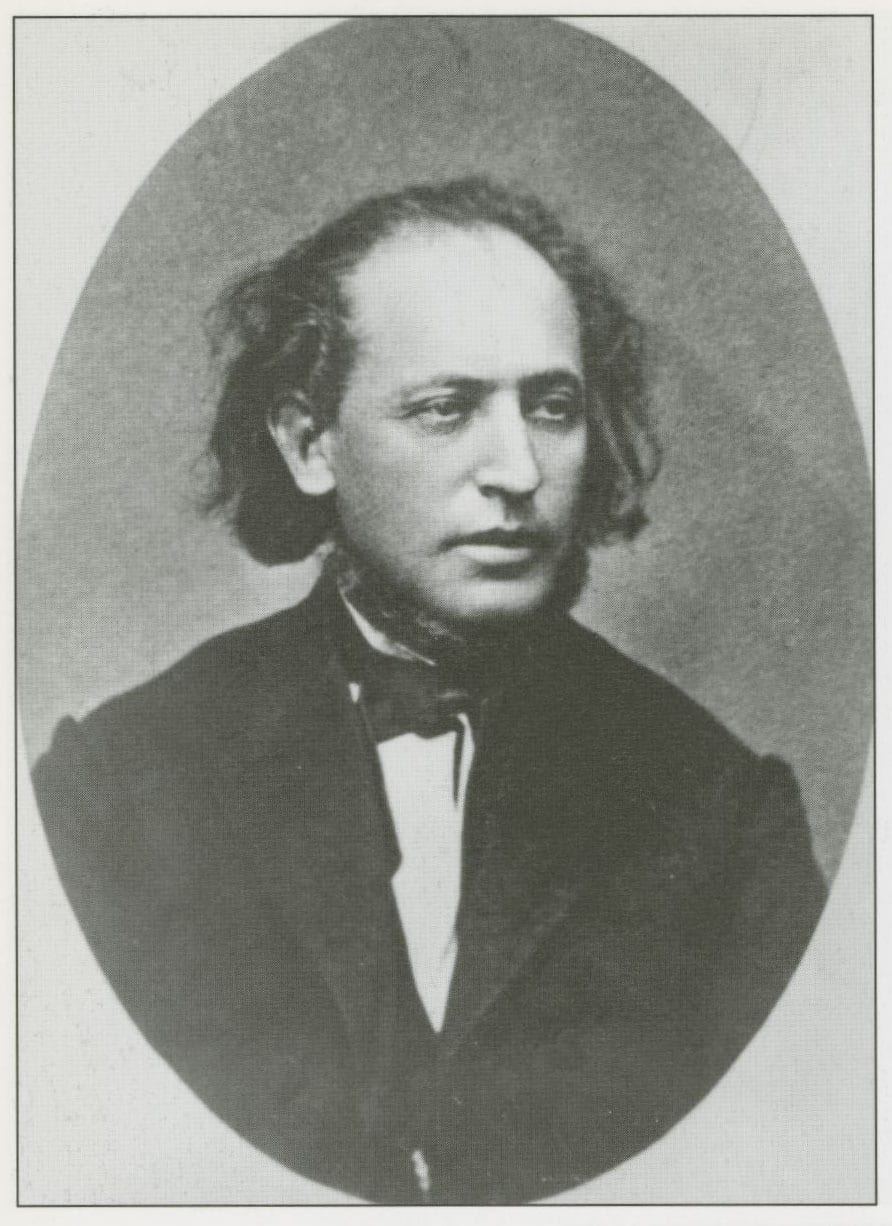

Enter Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise

During this time of questioning, 1846, Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise emigrated to the United States. His first congregation in the United States was the first to count women as part of a minyan and allow women and men to sit together in family pews in the synagogue. However, Wise was not always met with acceptance. These ideas were quite radical for the time and while working in Charleston, S.C., an altercation broke out between Wise’s opponents and his defenders. The sheriff was called while Wise was removing the Torah from the Ark (an ornamental chamber that holds Torah scrolls inside the synagogue).

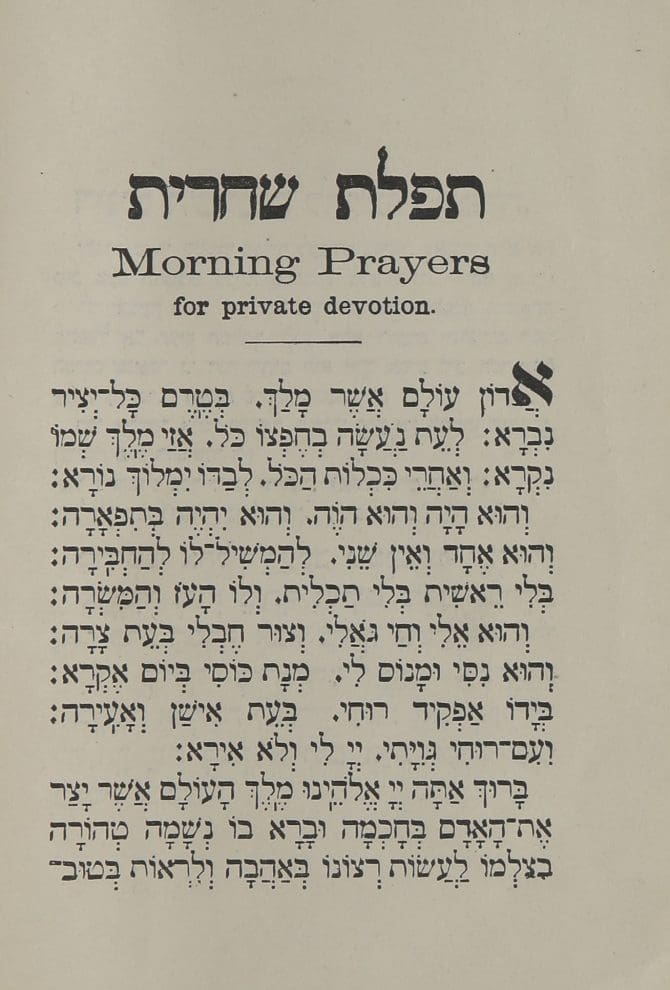

In 1847, Wise served on an advisory committee to the congregations of the country. That spring, Rabbi Wise submitted his prayer book, Minhag Amerika, for use by all the congregations of the country. Most congregations in America’s western and southern states adopted Minhag Amerika. Rabbi Wise had a strong desire for union across the country. So much so that years later, in 1894, when an updated Union Prayer Book was published, he put his ego aside and voluntarily retired Minhag Amerika from his own congregation.

The Trefa Banquet

Rabbi Wise moved to Cincinnati in April 1854 after being given a lifetime appointment from Lodge Street Synagogue. Lodge Street Synagogue was home to K.K. B’nai Yeshurun, a German Jewish immigrant community. Soon after he moved to Cincinnati, Wise began publishing his newspaper, The Israelite. In 1866 he began the planning and organization of the Plum Street Temple. Several years later, in 1875, Hebrew Union College opened its doors to rabbinical students. In a famous incident, the first graduating class gathered for a banquet. When it was discovered that some of the food was non-Kosher, or tref in Hebrew, many were vehemently opposed. This was far from traditional Jewish practice. Wise refused to condemn the food and this started the split we have today between Reform and Conservative Judaism.

Wise was married to Therese Bloch, sister to the founder of Bloch Publishing Company. They had 10 children. After Bloch’s death, Wise married his second wife, Selma Bondi, and they had four additional children.

Wise’s contributions to Judaism cannot be overstated. At his death in 1900 he was called “the foremost rabbi in America.”

To view more of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise’s work, please visit our Digital Library.

Bibliography

- Temkin, Sefton D. Isaac Mayer Wise. Shaping American Judaism. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Fine, John S and Frederick J. Krome. Jews of Cincinnati. Charleston, Arcadia Publishing, 2007.

- Sarna, Jonathon D., and Nancy H. Klein. The Jews of Cincinnati. Cincinnati, Center for the Study of the American Jewish Experience, 1989.

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Mayer_Wise

Add a comment to: Throwback Thursday: Cincinnati’s Rabbi Wise Was a Leader in Changing Jewish Traditions