Written by Ann Driscoll, Senior Library Services Assistant, Downtown Main Library

Written by Ann Driscoll, Senior Library Services Assistant, Downtown Main Library

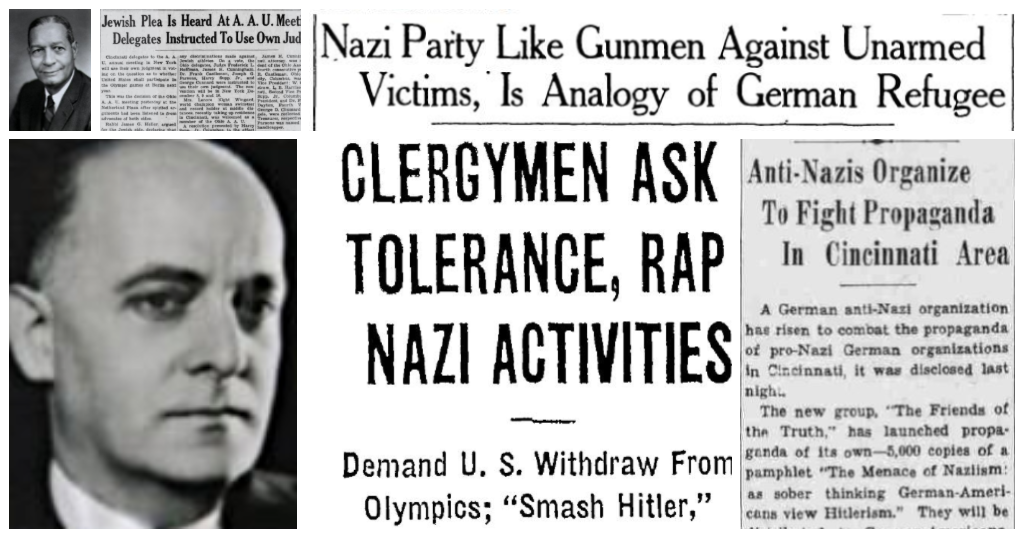

In 1934, just one year after Hitler seized power in Germany and seven years before the U.S. entered World War II, some Cincinnatians were already protesting Nazism and calling it out for what it was: anti-Semitic, racist, imperialist, and violent. From the local German immigrants who denounced Hitler in 1934 to the Jewish leaders who successfully ousted a City Councilman suspected of Nazi sympathies in 1935, local folks spoke out early and boldly. Thanks to the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County’s collection of local newspapers accessible via electronic databases, opens a new window, microfilm, and bound volumes, we can remember this history of foresight and action.

Pamphlets, Protests, Lectures, Boycott Calls

In 1934, local German immigrants distributed 5,000 pamphlets called, "The Menace of Nazism: as sober thinking German-Americans view Hitlerism.” The group was formed to protest local pro-Nazi groups like the Friends of the New Germany, opens a new window who they described as “transplanting to American soil the religious, racial, and class hatred upon which Nazi rule in Germany is based.”

Although the anti-Nazi German group didn’t reveal all of their members out of fear that relatives still living in Germany would be retaliated against by Nazis, a few of their members went public: August Hamelberg, August Hauck, Fred Bender, and John Wainz.

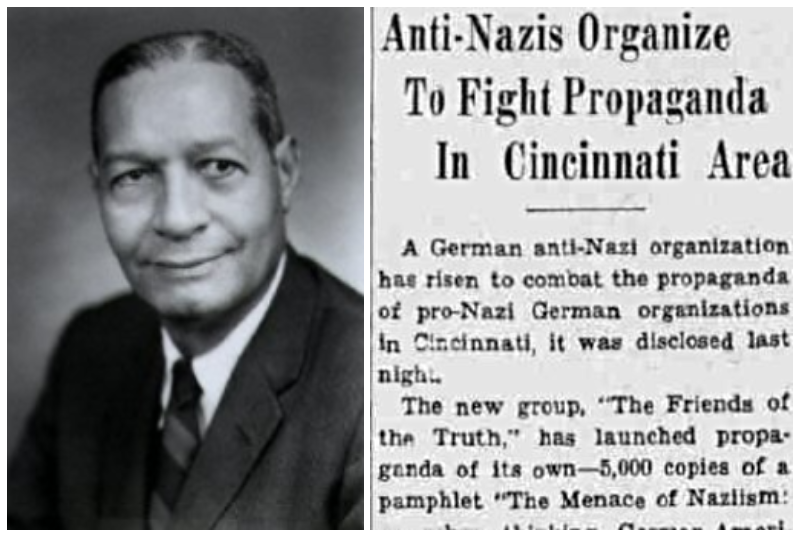

In August of 1935, Cincinnati’s first open-air anti-Nazi demonstration was held downtown at the Guilford School, attracting about 300 people. The protest was held by the Cincinnati Provisional Anti-Nazi Committee on a day of international protest. Protestors held signs bearing confrontational, aggressive slogans like “Smash Hitler.” “Keep the Swastika Out of America,” “Catholics, Protestants, and Jews Fight Hitler Terror.” Speakers included Rev. Emil Klotz, pastor of the Auburn Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church; Theodore Berry, president of the NAACP; and Julius Tietz, secretary and treasurer of the Ohio State Board of Education.

In 1935, the Netherland Plaza hosted a lecture by Gerhart Seger, a former Reichstag member and concentration camp escapee. In his speech, he compared the Nazis to "gangsters" and offered an analysis of Third Reich leaders, including Hitler about whom he warned: “Beware of that man; he believes every word he says.” The local committee that welcomed Seger included Charles P. Taft II and Rabbi James G. Heller.

Debates took place over the participation of the U.S. in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. In October 1935, Rabbi James G. Heller debated Friends of the New Germany leader, Henry Klohe in arguing that the U.S. should boycott the Berlin Olympics.

Throwing Nazi Sympathizers Out of Office

Anti-Nazism in Cincinnati not only took the form of protests and debates; it had real political teeth. The outcry over the Nazi rally at the German Day festival at Coney Island in August of 1935 illustrates this, as one elected official lost his seat the following election in part due to the backlash against his attendance at the rally.

German Day was an annual celebration of German heritage. Whereas the swastika had been banned in prior years, the picnic in 1935 featured thousands of marchers wearing Nazi armbands, the singing of the Horst Wessel song (the official Nazi song), and the flying of the swastika alongside the American flag. Ludwig Thon, the editor of the Cincinnati Freie Presse spoke at the festival, and in his speech, he attacked the press, claiming that reports about the persecution of minorities in Hitler’s Germany were overblown and hypocritical.

The American Israelite, opens a new window published a riveting, anonymous, first-person account by a Jewish journalist who attended the event and commented on the “incongruous” nature of its festivities: “Only good feeling, good food, happy faces, and the swastika,” the writer said sharply. The Israelite writer went on to describe Nazi ideology as “…racial purity and the elimination of the Jews; Imperialism, with the Nazi philosophy being carried to all countries, the cutting off of all opposition by a government-controlled press, and the imprisoning of political opponents.”

Backlash against the rally was swift, and it was targeted specifically against the elected officials who attended the rally, including Dr. Glenn Adams, a City Councilman who served as Officer of the Day for the event.

The Catholic Telegraph argued, “We think the Nazi demonstrations should absolutely be squelched and repudiated by the other German groups of Cincinnati.”

I.M. Rubinow, the national executive secretary of B’nai B’rith published a public statement called “The Nazi In Our Midst” admonishing the elected officials who attended for giving “tacit approval all of this by sitting on the speakers’ stand and by not once publicly indicating any disgust with these proceedings.”

The American Israelite published an editorial called “Defeat Dr. Glenn Adams,” and Israelite editor and publisher, Henry C. Segal issued a statement refuting the rally participants’ denials of Nazism.

The campaign against Adams apparently worked: he was defeated the following November. Lashing out after the election, Adams claimed that he was the one being persecuted, that German-Americans had a right to defend Nazism, and that Jews had brought whatever persecution they were experiencing upon themselves. The American Israelite remarked that Adams’ defeat represented a victory for Cincinnati’s “reputation for communal harmony.”

From protests to lectures to pressure campaigns targeting elected officials suspected of Nazi-sympathizing, early anti-Nazi activity in Cincinnati is preserved in the local newspaper resources at the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

Add a comment to: “SMASH HITLER!”: Local historical newspapers show how Cincinnatians protested the rise of Nazism in the 1930s