Written by Kevin Welch, Digital Services Assistant, Genealogy & Local History Department, Downtown Main Library

Written by Kevin Welch, Digital Services Assistant, Genealogy & Local History Department, Downtown Main Library

On the first Thursday of each month, our Genealogy & Local History Department "throws back" to a time in Cincinnati's history that is featured in our Library's wide-ranging collection of more than 9 million materials.

Cincinnati is well-established in popular memory as a river city, but it was the humble and oft-forgotten Miami Canal that fueled her prosperity and helped establish her as the nation's sixth-largest city.

Founded on the Ohio River in 1788, Cincinnati spent her early decades otherwise cut off from the rest of the country. Overland travel to the East Coast was blocked by the Appalachian Mountains, and access to the interior of the state was incredibly difficult. The region’s farms were unable to get their goods to the city, and the city’s workshops were unable to ship their finished goods east.

The young city’s future prosperity depended on an improved transportation network. It took the state legislature 20 years to secure funds and survey possible routes, but plans were eventually drawn for the building of two canals that would connect Lake Erie with the Ohio River. The Ohio and Erie Canal would run between Cleveland and Portsmouth, and Miami and Erie Canal between Toledo and Cincinnati.

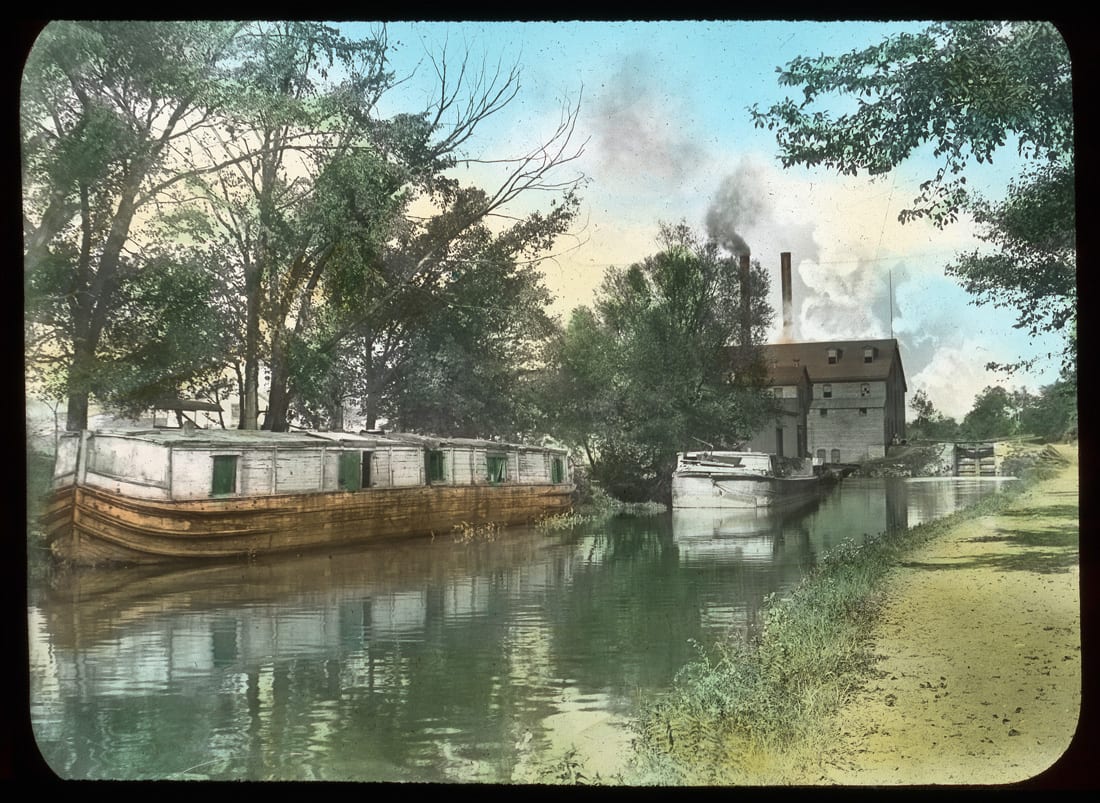

Canal, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Canal, Cincinnati, Ohio.

A Growing City

Construction of the Miami and Erie Canal began in Middletown on July 21, 1825. An army of 1,000 workers dug the canal trenches, which were four feet deep, 40 feet wide, and lined with sandstone. Changes in grade along the route required the construction of locks, reservoirs, and feeder canals. The stretch between Cincinnati and Dayton opened in 1828, and by 1832, 1,000 people a week were traveling between the cities. Completed in 1845, the 274-mile-long Miami and Erie Canal allowed raw materials to flow into the city, and finished goods to flow out. The canal led to a boom in immigration, and Cincinnati’s population nearly doubled between 1830 and 1840.

Traveling by Canal

Canal boats were known as packets. These distinctive flat-topped vessels varied in length but were built to a standard 14-foot width to accommodate two-way travel on the canal. The largest could carry 60 passengers and offered sleeping quarters for overnight journeys. A 10-foot wide towpath accommodated the horses or mules that pulled the packets, which could travel at a speed of four or five miles per hour. The introduction of a safe, comfortable means of transport allowed thousands of immigrants and pioneers to move into the interior of the state, and the canal was filled with freight boats and passenger ships.

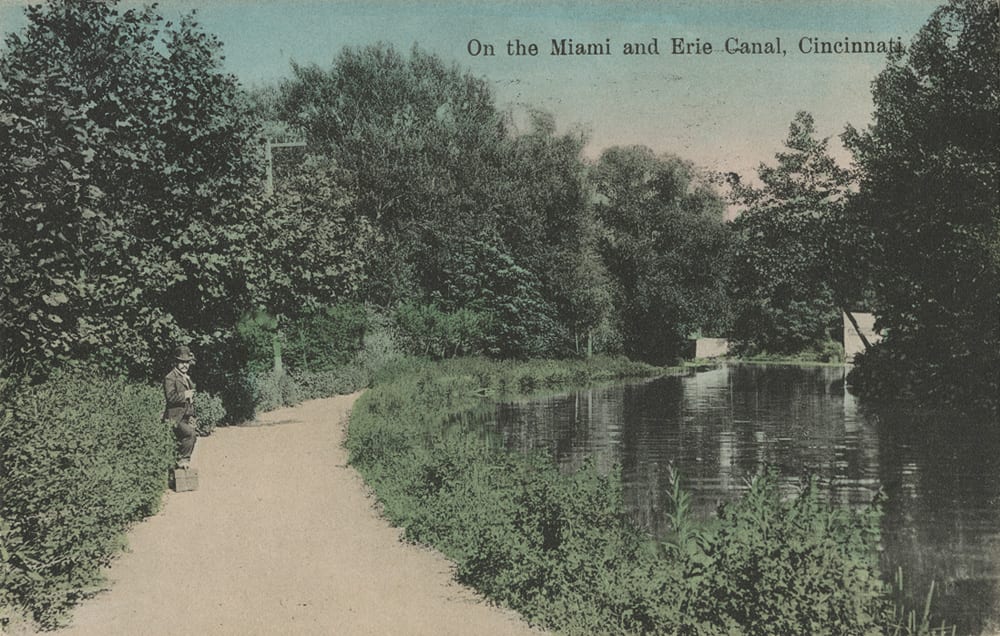

On the Miami and Erie Canal, Cincinnati.

On the Miami and Erie Canal, Cincinnati.

Arriving in Cincinnati

The 66-mile route between Dayton and Cincinnati took 24 hours to complete and roughly followed the course of present-day Interstate 75. What would it have been like to arrive in Cincinnati on the Miami Canal? Southbound passengers would have observed changing scenery as pastoral views and homesteads gave way to industrial outposts. At Lockland, a 48-foot change in elevation necessitated a series of locks, which in turn supported a host of water-powered mills built at the canal's very edge.

The Locks, Lockland, Ohio.

The Locks, Lockland, Ohio.

After passing through the locks, the journey continued south through St. Bernard, to an elevated aqueduct that ushered the packets across Mitchell Avenue. The image below shows the Carthage Pike Bridge, now Vine Street, crossing over the Miami and Erie Canal.

Carthage Pike Bridge over the Miami Canal in St. Bernard, Ohio.

Carthage Pike Bridge over the Miami Canal in St. Bernard, Ohio.

At the foot of Clifton Avenue, two basins adjoined the canal to help maintain water levels, one of which President William Howard Taft reportedly swam in as a boy. Pedestrians following the canal's towpath here would have an opportunity to overlook an artificial waterfall directly across from Spring Grove Cemetery as it diverted excess wastewater into Mill Creek.

Canal overflow, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Canal overflow, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Beyond the spillway, the canal wound its way past the base of Mt. Storm Park, as seen in the image below. The sign on the front of the boat reads “Ludlow Grove.”

The Miami and Erie Canal at the foot of Mt. Storm Park. Photo by Elmer L. Foote.

The Miami and Erie Canal at the foot of Mt. Storm Park. Photo by Elmer L. Foote.

Continuing south past Cumminsville and Camp Washington, riders arrived at one of the busiest landings on the canal at Brighton, home to some of the nation's largest distilleries. Grains and whiskey were common freight, along with ice, pork, and lumber. By 1850, as canal activity peaked, the neighborhood had earned a reputation for harboring a rough crowd of characters among the roustabouts, laborers, and canal drivers.

Further downstream, canal boats cruised past Music Hall as they approached the same bend at Plum Street still visible today on Central Parkway. “Canal Street” as it was formerly called, represented the dividing line between downtown and Over-the-Rhine. In stepping across the canal, the visitor entered “at once into the borders of a people more readily happy... more closely wedded to music and dance, to song, and life in the open air,” as described in Kenny's 1879 Illustrated Guide.

Men sitting on a canal boat.

Men sitting on a canal boat.

At Sycamore Street, the canal turned sharply and entered the Lockport basin. Here, packets unloaded passengers and cargo. The last stretch of the canal followed the path of Eggleston Avenue. The difference in elevation required 10 locks to deliver packets to the Ohio River below. Most journeys terminated at the Lockport Basin due to the inconvenience of passing through the locks, so this section fell out of use after 1863.

The Canal Today

The canal was finally abandoned after the great flood of 1913. It had been in decline for years due to the success of the railroads, which were introduced in the 1850s. The canal remained a health hazard for years and was eventually drained and dug into a subway tunnel along a two-mile section through downtown. The image here provides a view north of Findlay Street, during the subway construction in 1921.

Old canal and rapid transit north of Findlay Street.

Old canal and rapid transit north of Findlay Street.

The subway was never completed, but the boulevard built on top of it was a great success. Central Parkway was dedicated in 1928, and its broad, divided course retains a vestige of the canal's former presence and character.

Bibliography:

- Miami and Erie Canal by Bill Oeters and Nancy Gulick

- The Waterways of Southwestern Ohio: Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal, Whitewater Canal, Miami Canal, and Ohio River Navigation by David A. Neuhardt

- The Miami and Erie Canal and Its Relation to the City of Cincinnati by the Association for the Improvement of the Canal

- Canal and subway construction photographs from the digital library of Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library

Stop by the Cincinnati Room at the Downtown Main Library to view letters, photos, and other artifacts from the Library’s Abraham Lincoln collection. The exhibit was created in connection with this year’s Mary S. Stern lecture featuring Doris Kearns Goodwin.

Add a comment to: Throwback Thursday: Take a Trip on the Miami and Erie Canal